Over the last few years, the internet saw the return of trends ranging from the 90s, noughties, and beyond. Among them, "Y2K" was another term that got thrown around a lot in association with throwbacks. Talks of its resurgence surfaced as early as 2016, so how is it still so relevant in 2022?

With a mix of frustration at hearing the word so often and disbelief that the era's revival lasted that long, I decided to look into some of this year's biggest fashion trends like micro-mini skirts and bedazzled low-waisted jeans. As it turns out, they belong to another aesthetic called "McBling," also known as Y2K's "hungover cousin."

First coined by Evan Collins, McBling does, in fact, overlap with Y2K for a couple of years. However, the two are, as Collins put it, "diametrically opposed" in stylistic qualities. The former saw Von Dutch trucker hats, Juicy Couture velour tracksuits, baby tees with cursive fonts, and anything that screams "bling," influenced by celebrity culture and aspirational luxury. Meanwhile, the latter named after the Y2K bug is characterized by shiny clothes, tight leather materials, silver eyeshadow, translucence, and more things propelled by tech optimism.

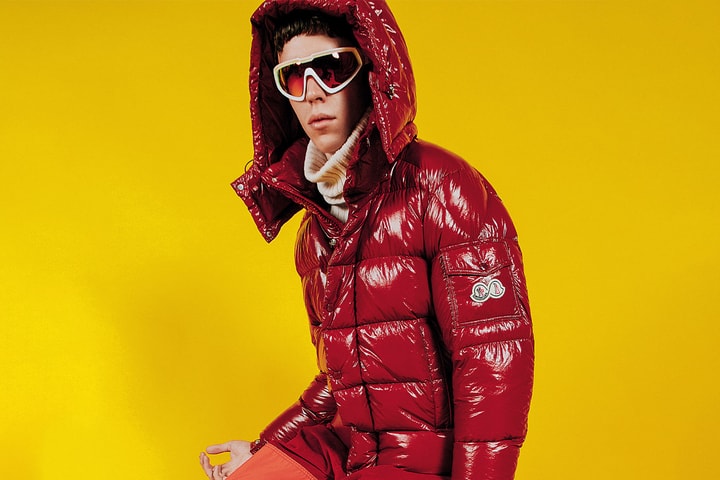

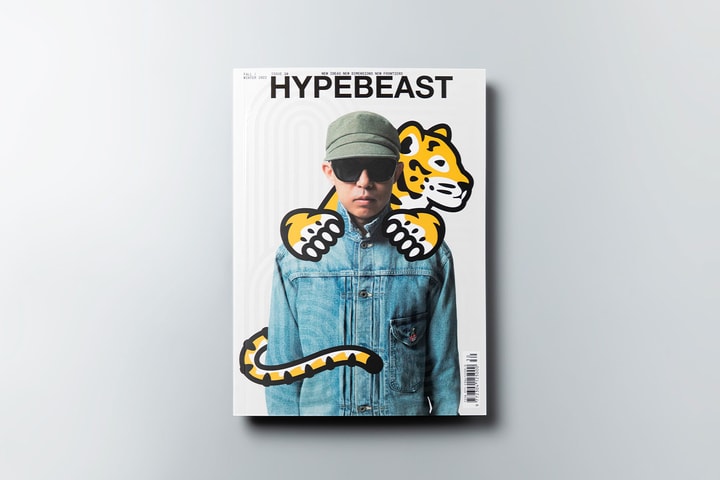

Considering the common mix-up, HBX Journal connected with Collins and Froyo Tam, designers who run the archival Twitter account Y2K Aesthetic Institute and the research platform CARI. From ongoing research work to observations within the creative sphere, the duo offers insight into the change in trend cycles, misconceptions of periods, and what they hope to achieve with CARI. As a joint effort with the duo, we also produced images displayed throughout the article as a nod to the Y2K aesthetic.

How CARI Began

Collins and Tam were both part of "Vaporwave" Facebook groups in 2015, with the former's earliest involvement dating back to the early 2010s. Despite being only nine years old in 1999, the era's excitement about futurism and tech optimism remained apparent to Collins and so began his investigation. What fascinated him was the idea of trying to understand the visual zeitgeist of a time--Vaporwave being that during the 80s and 90s with sunsets, palm trees, and synths grid motifs.

For Tam, the inspiration came from looking at the explosion of web design from the late 90s to the early 2000s that coincided with the rise of Adobe Flash on archive.org's Wayback Machine. Now that Adobe has discontinued support for Flash, she emphasizes the importance of recording past designs, "It's the synthesis of visual languages informing not just graphic design, but also visual motifs played out in architecture, interior design, and industrial design."

Short for "Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute," CARI serves to catalog post-modern design cycles from the 1970s to today. "When we first started this research, there was a fair amount of work on earlier aesthetics like 'Art Deco' and 'Mid-century Modern', but the 1970s onwards right up until now just isn't well understood as much," Collins explains, "It's trying to help educate ourselves and the public about the more intricate nature of design movements and their context, especially social, cultural, and economic aspects of the time."

From Reddit and Facebook to eventually Tumblr, Instagram, Twitter, and now an independent site for CARI, it seems that the duo's archival work has only grown in scale. While this brings them closer to the goal of having an academic framework that helps defines trends and encourages people to submit their findings, more exposure has led to instances where what they put out gets taken out of context.

TikTok Virality and Faster Trend Cycles

"During the pandemic, you had this huge explosion of core suffix-related stuff [on TikTok]–'cottagecore' being a great example of that. It was these lifestyles that people started adopting when most of us were in lockdown," Tam recalls. Media outlets would then take it as an opportunity to create content out of what's viral. "There's a craze for cycling through content as fast as possible and a weird giant machine that pumps out articles," Collins adds.

The aesthetic "Indie Sleaze" appeared in a dazed article in October 2021. For about two months that followed, not only did other editorial platforms tap into the topic, but fashion resellers like Depop also jumped on the bandwagon and used it as a trending tag. Similarly, another aesthetic called "Whimsigothic" blew up on TikTok. Still, its moment of fame was also fleeting as it got burnt out by the many articles generated around it.

Tam describes the phenomenon, "It's easy to create something that's sensationalized, boiled down, and studied to its surface level, while most of the time, disregarding the societal context that helped shape it in the first place." Such has led to increasingly short-lived trend cycles, to which she says, "It's an acceleration brought forth by the acceleration of capitalism." Elsewhere, talks of the revival of mid-2010s Tumblr have also surfaced recently, veering from the previously-understood 20-year trend cycle. Collin adds, "Because the fundamental structure of media and how it operates now in culture is so much faster, everything just cycles constantly."

Y2K Versus McBling

Considering the large quantity of content with way shorter duration that's put forth by social media algorithms, audiences are left with shorter attention spans and, sometimes, shallower interpretations of information. As such, misconceptions manifest, which is perhaps a reason in the case of the confusion between Y2K and McBling.

"[McBling] was a very conservative, reactionary, and regressive time. It wasn't a lot of fun to live through," Collins recalls about the era that was "very obsessed with status, aspirational wealth, luxury, and had a hollow, nihilistic vibe to it." Y2K, on the other hand, "had a real sense of optimism about the future even if it was misguided." Emphasizing the importance of more nuanced and holistic discussions of the context behind time periods, he mentions the negative associations with McBling, "It's how celebrities were treated and how things were heavily-gendered."

What CARI does

While there's not much that can be done about the rate information spirals, the duo tries to at least give economic context for the findings they put out with CARI. "It's just a matter of us creating an atmosphere where we can help provide a platform to present these aesthetics with much deeper analysis in the public sphere," Collin says.

As part of their research, Collins and Tam do a lot of image scanning and reach out to designers. Besides finding relevant articles from the time, they try to source original accounts from the 1980s and 1990s with people who have firsthand experience of working in the era to help illuminate what was happening to understand why certain aesthetics emerged or disappeared to a much greater degree.

In addition, the duo's Discord server looks into emerging styles. Collins particularly appreciates the revival of "Alt Psychedelia," a corporate appropriation of hippie and psychedelia from the 60s and the 70s. Meanwhile, Tam favors the eyewear brand Oakley's current branding, which she describes as having an "Apple, Garamond utopian scholastic vibe" reminiscent of condensed Serif fonts found in Macintosh ads of the 80s and 90s.

When asked about resurgences they hope to see, the two continue to express their penchant for 2000s aesthetics with mentions of translucent blobjects and more experimental designs. "[The iMac G3] is one of the greatest landmarks of Y2K industrial design pieces," Tam says. Apple's curvy, translucent computer made in 1998 also inspired the colors of the Nintendo 64 video game console and the Kodak DC240i Zoom cameras. For about two years, it appeared everywhere in the industrial design and fashion world, including the Alcatel Gel phone and Karim Rashid's chess pieces, before it got oversaturated and completely vanished after 2001.

In terms of design, Collins is keen to see more "playfulness, craziness, and tackiness." The scarcity of diverse designs is especially apparent in the universal language of contemporary Air BNBs called "Airspace," defined by gray laminate floors and a homogenous aesthetic that permeates everything else. Describing an interior magazine from 1997, he says, "That atmosphere and freedom of being able to create and fail is something that’s so gone now." Agreeing, Tam adds, "You just end up with a lot of copycats designs because everyone is in a little bit of a panic due to the lack of money." A vicious cycle of economic forces and a fear of failure seem to have led people to focus on production speed rather than invest in the designs in the first place. She continues, "Designers need more budget so we can actually go buck wild crazy sh-- happening everywhere again."